A beautiful sight to behold, the giant clam, which enjoys the warm waters surrounding the Great Barrier Reef, is the largest living bivalve mollusc. At times weighing more than 200kg, these bottom feeding behemoths have an average lifespan of around 100 years in the wild.

Having a rather settled nature from the outset, the giant clam will find its home on the reef and remain there throughout its entire life. Here it feeds on passing plankton, which it syphons from the water it draws through its large opening.

The giant clam also feeds on the sugars and proteins produced by the billions of algae that live within its tissues. In exchange for this plentiful supply, the clam offers the algae a safe home and regular access to sunlight for photosynthesis.

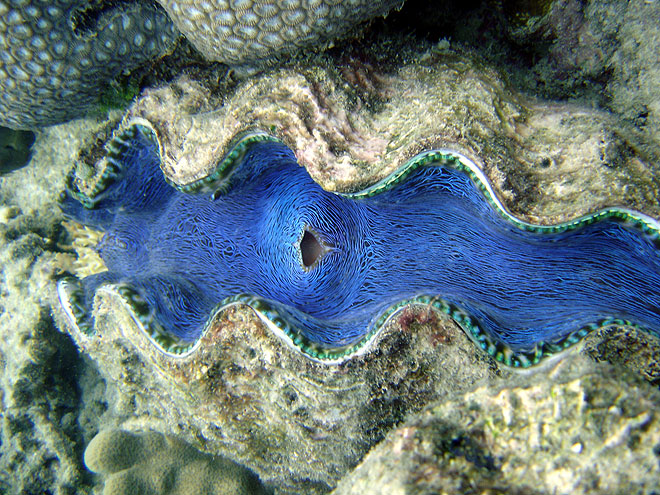

The colours of this pelagic monster are also varied and alluring, although it’s impossible to distinguish particular species from this trait alone. Ways of distinguishing clam species when exploring the Great Barrier Reef are by noting the size and ridges on the external part of the shell.

Interestingly, it is the algae within the clam that provide for much of its physical beauty, as the clam’s pigmentation figures in stark contrast to that of the algae’s. Colour can also indicate the health of the clam, with dying algae bleaching to a bright white.

The bright coloured circles located on the clam’s flesh are called iridophores, which direct sunlight onto its mantle. If the giant clam senses there’s not enough light filtering through to the algae, it extends its mantle out of its shell and reduces this colour pigmentation to offer it more.

Regarding its sex, each giant clam starts out as a male before becoming a hermaphrodite (producing both eggs and sperm). This trait allows them to reproduce with any member of their species, thus eliminating the burden of finding a compatible partner. The largest clams can release up to 500 million eggs at a time.

Unfortunately for this rather handsome looking bivalve, its abductor muscle is considered a delicacy, which has landed it a place on the increasingly diverse list of vulnerable species. The Chinese also consider this muscle to be an aphrodisiac.

There’s also a common myth in the South Pacific, that’s entirely invalid, of the giant clam being able to trap and even devour a passing diver from time to time. Firstly, its shell moves far too slowly to cause distress to humans. Furthermore, there’s never been a recorded incidence of human death by clam.